“Our scientific power has outrun our spiritual power. We have guided missiles and misguided men.” – Martin Luther King Jr., Strength to Love (1963) [6]

Modern society marvels at its technological prowess, yet it continues to struggle with age-old moral and social dilemmas. Humanity may be far more advanced technologically than even a few decades or millennia ago, but “if we look at morality, it’s not even certain that there is any progress at all”. Indeed, the same fundamental conflicts and ethical puzzles that preoccupied ancient philosophers still confront us today. Throughout history, the inability of human groups to sustain long-term cooperation has repeatedly led to wars, social strife, and even conflict with nature. In our own time, this failure to collaborate on a global scale has become an existential threat. Issues like climate change, pandemics, and resource depletion demand unprecedented unity, yet nations and communities remain divided by incompatible values and interests. For example, leading scientists warn that unchecked population growth and resource overconsumption are driving humanity toward ecological collapse within decades [7]. Mitigating such a catastrophe requires global cooperation – a prospect that seems increasingly out of reach when geopolitical tensions are causing international coordination to stall. Recent reports show that conflict-related deaths have spiked to the highest levels in 30 years and a record 122 million people were displaced in 2024 (double the number a decade prior) [8], highlighting the human cost of our failure to resolve deep-seated value clashes. What lies at the root of this worldwide crisis of values? And might there be a principled basis on which humanity can forge a shared value system to enable the cooperation needed to avert disaster?

The Value System Roots of the Global Crisis

Every decision we make rests on some conscious or unconscious value judgment. It is no surprise, then, that many contemporary thinkers – from social philosophers to economists – have argued that today’s global problems are, at their core, problems of values. In other words, we are facing a crisis of values on a global scale. Jürgen Habermas, for instance, has long pointed to the “disruption of normative structures” as a threat to social integration [2]. Martha Nussbaum and others have similarly lamented how a relentless, growth-centric form of capitalism has eroded older ethical frameworks, prioritizing market success over compassion and community. In the words of one commentator, “market values have steadily infiltrated societal values” to the point that value itself is often equated with profit, while social and environmental goods are disregarded as “worthless” if they cannot be monetized [3]. This infiltration of market ideology has coincided with rising inequality, alienation, and ecological destruction [3] – all symptoms of a deeper values breakdown. Social surveys in recent years underscore the malaise: despite material advancements, reported loneliness and disconnection are widespread (about one in six people globally experiences chronic loneliness) [4], and trust in institutions and between communities has deteriorated in many countries. It is increasingly clear that without some renewal of shared values, efforts to tackle large-scale crises will remain fragmented.

Observers across disciplines now speak of a pervasive modern value crisis [3]. Some see addressing this crisis as the sine qua non for humanity’s survival. If our societies could coalesce around a common core of values, perhaps we could achieve the collective action needed to solve problems like climate change, pandemics, or global poverty. However, this is easier said than done. Human history offers little evidence of any enduring, universal value system. On the contrary, values have always been plural and local: what one culture or era upholds as virtuous, another may condemn. In small, close-knit communities of the past, people could more easily unite under a shared ethos, but whenever larger masses have had to cooperate, value differences have proven to be a stumbling block. There is a nostalgic notion that a return to “old-fashioned” virtues would repair the moral fabric of society. Yet even the revered values of bygone eras often failed to prevent conflict and injustice on a wider scale. If those traditional small-community values had truly been sufficient, we would not find ourselves in the present predicament. This suggests that the roots of today’s value crisis run deeper than merely forgetting old virtues. The fundamental problem may lie in the subjectivity of our values – the fact that what we value is largely based on arbitrary or culturally contingent premises, rather than any objective standard. Lacking a common point of reference, different people and groups inevitably assign different values to the same things, and there is no impartial way to resolve these disagreements. In effect, everything becomes relative, and debates become zero-sum struggles of wills rather than reasoned consensus.

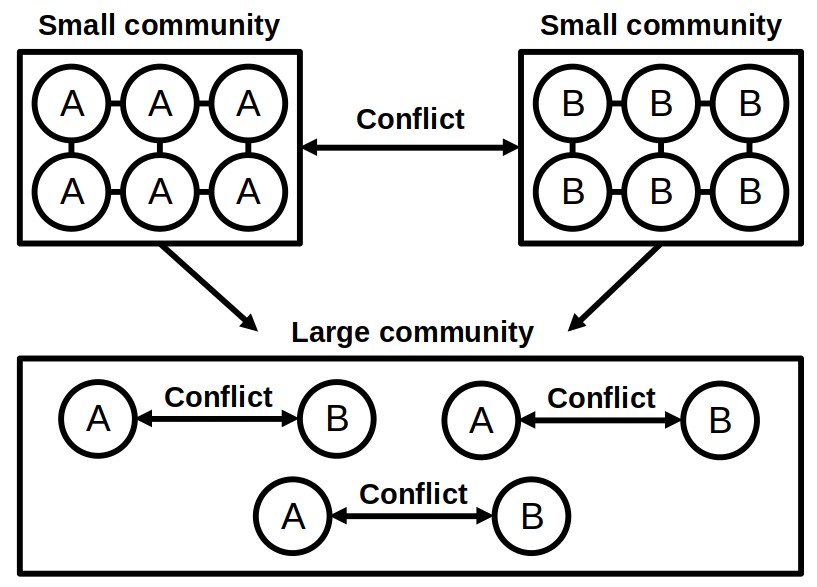

The consequences of this relativity have been visible throughout history. As societies grow and diversify, their members’ value systems tend to drift apart. Anthropological and sociological studies confirm that groups separated by geography or culture will evolve distinct norms and priorities over time. When such groups encounter each other, incompatible values can spark friction and conflict[5]. Entire wars and genocides have been fueled by irreconcilable religious or ideological worldviews. Even within a single society, if sub-communities develop divergent values (due to class, ethnic, religious, or political cleavages), social cohesion breaks down. The large, pluralistic nations of today often contain a patchwork of value subcultures, contributing to polarization and what sociologists call the atomization of society – individuals retreating into isolated units due to lack of a shared moral community. In extreme cases, a society can fracture from within, as mutual understanding gives way to mutual hostility. Studies indicate that conflict is especially likely when groups not only compete for resources or power but also “have incompatible values” at stake [5]. It follows that lasting peace – both within and between societies – hinges on some level of compatibility among value systems. This realization prompts a critical question: Can we define a set of values that is truly compatible across humanity? And if so, how might we ground such values in a less subjective, more universally acceptable way? To approach these questions, we must first clarify what we mean by “value” in this context.

The merging of homogeneous groups with value systems A and B causes the atomization of the community if A and B are not compatible with each other. Large homogeneous communities also lose their homogeneity over time because value systems change, develop evolutionary, and become more diverse, which can lead to social tensions.

What Is “Value”? Defining the Term

In order to discuss a “value crisis,” it is important to pin down what we mean by value. Philosophers use the term in various ways, but here we take an analytical approach: let us define value as a quantity assigned to things, representing their importance or worth. More formally, we can think of value as a function that maps any given entity or pattern to a number. The word “pattern” is used in a very general sense – it could be a physical object with certain structure and properties, a specific action or behavior, a configuration of ideas, even an abstract construct like a mathematical formula or a melody. In short, anything that can be described or imagined – any pattern of information – could be assigned a value. The value function would then produce a numerical “value score” (or value quantity) for that pattern.

Of course, this definition by itself says nothing about which numbers should be assigned to which things. To make the concept useful, we need the value measure to meet some key requirements. Ideally, a value function should be:

- Universal – it should allow the comparison of very different things on a common scale. In other words, the value of a human life, a work of art, and a sum of money should, in principle, be commensurable in this framework (even if it feels philosophically uncomfortable to compare them). A universal value metric would enable trade-offs to be evaluated rationally: e.g. how many dollars is a life “worth” when assessing safety measures? Currently such comparisons are often made implicitly, but a transparent universal scale would make the judgments explicit.

- Deterministic and measurable – the value of something should be determined by well-defined parameters or features, capable of being measured or calculated. This contrasts with value judgments that depend on whims or subjective feelings. If two observers have the same information about an entity, a deterministic value function would assign the same value, avoiding random or impulsive variation.

- Context-independent (objective) – the value should not directly depend on extrinsic factors like who is observing or the prevailing cultural opinion. Instead, value should be assessed based on the intrinsic characteristics of the thing itself. In practice, this means the value function should be grounded in the object’s inherent structure or information content. For example, if we value a painting, an objective approach would try to derive value from properties of the painting (its complexity, symmetry, etc.) rather than the viewer’s personal taste or mood.

- Inherent – this concept overlaps with objectivity. Inherent value means the worth of something is built-in, stemming from its internal qualities, not from external labels or opinions. If value could be inherent and universal, it would provide a stable foundation: everyone, no matter their background, would evaluate things using the same fundamental yardstick. In reality, we might relax these strict conditions and accept a system that approximates universality and objectivity, even if it’s not perfect. But these criteria outline an ideal benchmark.

To illustrate, think of how we assign monetary value to goods. Money is a crude but widely used attempt at a universal value measure. We price items in dollars, euros, etc., allowing comparison between, say, a loaf of bread and an hour of labor. The price is a single number reflecting value in trade. However, money’s objectivity is only partial: prices emerge from the collective subjective judgments of buyers and sellers, and they fluctuate. If value were truly inherent and objective, two identical items would always fetch the same price, and predicting price changes would be straightforward – which is far from the reality. Still, the concept of pricing hints at how a more universal value system might function.

In summary, “value” in this discussion is not just an abstract idea of goodness or beauty; it is something we imagine could be quantified and standardized. This sets the stage for examining how our current value systems – ethical, cultural, economic – fall short of that ideal, and how those shortcomings contribute to the value crisis.

Flaws in the Current Value Systems

Our inherited value systems (moral codes, cultural norms, religious doctrines, etc.) were not designed with the above analytical criteria in mind. Unsurprisingly, they exhibit several structural flaws when viewed through this lens. One major issue is the lack of a stable, objective foundation. Unlike physical measurements which have clear zero points and units (think of meters for length or degrees for temperature), most value systems do not define a universal scale with a zero origin. The “zero” of moral value is often ambiguous – what counts as having no value? Likewise, the upper and lower bounds of value are usually framed in qualitative binaries (good/evil, sacred/profane) rather than on a continuous numeric range. Many cultures reduce value judgments to a stark dichotomy: something is either good or bad, allowed or forbidden. This binary approach is a coarse simplification that lacks nuance. It allows us to rank some things as better than others in a broad sense, but it fails to capture degrees of value. As a result, our moral evaluations often cannot accommodate incremental differences.

Consider a common claim like “all human lives are equally valuable.” This expresses a noble ethical conviction – the intrinsic dignity of each person – but as a literal statement in a value system, it creates a logical conundrum. If every life has exactly the same value, then saving one life or saving a million lives would ostensibly be of equal value, which is nonsensical from a decision-making perspective. In reality, we do prioritize saving larger numbers of people in emergencies, implicitly acknowledging that quantity matters. Yet our language of values struggles to articulate that, because it’s stuck in categorical terms (life = infinitely valuable) rather than scalable metrics. A robust value system would allow additive comparisons – e.g. that saving two lives is twice as good (in some unit of value) as saving one life. Such additivity requires a quantitative scale, not just categories.

A~B ⇒ érték(a) ~ érték(B)

Mathematical description of local stability or continuity.

Another flaw in everyday value thinking is the lack of continuity or local stability. Ideally, if two things are very similar, their values should also be similar. Small differences in merit should result in small differences in how we value them. However, many social value judgments ignore this principle. In practice, people often treat value in a discontinuous way – small improvements or deteriorations might not change an assessment until some threshold is crossed. We see this with moral praise and blame: doing some good often yields no more credit than doing no good, until one’s actions are seen as “good enough.” This is related to what mathematicians call strict monotonicity – if A is better than B in reality, a well-structured value function should assign A a higher value than B, even if the difference is slight. Yet human moral judgments frequently violate monotonicity. For instance, if one person donates $100 to charity and another donates $1,000, many ethical worldviews would not say the second person is ten times “more moral.” Qualitatively, both are considered to have done a good deed – and if anything, the one who gave $100 might be told “it’s not enough to make a difference” while the one who gave $1,000 might also be told “well, you’re still not solving the problem.” As the original author notes, society often treats goodness as if it were binary: either an action is deemed good enough to count, or it’s dismissed as worthless, with little gradation between. A volunteer picking up a single bag of litter might be cynically told, “What you did is negligible – it changes nothing,” which can discourage them from doing more. In a properly monotonic value system, more good should always be better than less good; even small contributions would register as a little better than none, encouraging cumulative effort. The absence of such scaling in our moral instincts can discourage incremental improvements and everyday acts of kindness, since only grand gestures are seen as truly valuable.

Closely related is the idea of subadditivity. In a logical value framework, the value of a whole should not exceed the sum of the values of its parts. In other words, combining two things shouldn’t magically create extra value beyond what the components contribute. (If anything, there could be synergies that make the whole slightly less than the sum, or exactly equal, but not more – this is what subadditivity implies.) Our economic transactions often follow this principle: buying items in bulk or as a bundle is usually cheaper (equal or lower total price) than buying each separately, never more expensive. Yet many moral frameworks violate subadditivity spectacularly. Consider the traditional Catholic doctrine that a single mortal sin is enough to condemn a soul to hell. Committing additional mortal sins doesn’t make you “more damned” – salvation is lost after the first, so in effect it’s an all-or-nothing value on the state of one’s soul. This creates a perverse incentive: a person who has crossed that line might reason that since they’re already bound for hell, they might as well indulge in more sin. When there is no gradation of “worse” beyond a point, the deterrent against piling on bad behavior vanishes. The result, as observed by theologians and philosophers, can be a slide into moral nihilism – a feeling that if one cannot be perfect, one might as well give up trying to be good at all. In secular contexts too, whenever we treat a certain offense or failure as utterly unforgivable or irredeemable, we may inadvertently remove incentives for improvement or partial compliance. A more nuanced value system, by contrast, would register degrees of bad and good, so that doing more harm would always be worse than doing less, and doing more good always better than a little good. Such a system would encourage continuous moral effort and discourage “all-or-nothing” thinking.

A < B ⇒ érték(A) < érték(B)

Strict monotonicity in the language of mathematics.

To summarize, our prevailing value systems are hampered by: (a) vague or subjective baselines (no agreed zero or unit of value), (b) coarse categories that collapse gradations into binaries, and (c) non-linear judgments that violate consistency principles like monotonicity and additivity. These flaws make our values “mathematically” and logically inconsistent, which in turn hampers rational discourse about trade-offs. When people do not share a common objective metric, debates over “what is better or worse” devolve into rhetoric and power struggle. The lack of an internal logical structure in value systems means they cannot be easily reconciled or aggregated across different people. Small wonder, then, that values differ wildly between groups and are resistant to change through argument – current frameworks do not allow precise alignment or compromise, only categorical acceptance or rejection. This diagnosis suggests that if we ever hope to resolve the global value crisis, we may need to reformulate values in a more systematic, quasi-quantitative way that addresses these structural issues.

Subjective versus Objective Values

The discussion so far implies a crucial distinction: subjective vs. objective values. In philosophy, subjective values are those that depend on personal or cultural attitudes – value is in the eye of the beholder. Objective values, by contrast, would have a reality independent of what anyone happens to think or feel – they would be facts that hold universally, like physical constants, if such things exist in the moral realm.

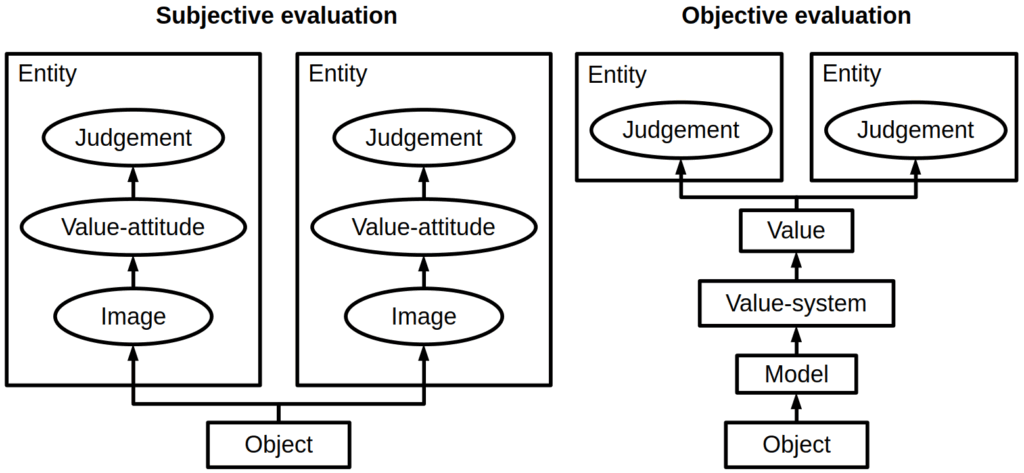

Our current value systems, as argued, are largely subjective. They evolved from human perceptions, emotions, traditions, and social agreements. A subjective (or context-dependent) value is one that changes depending on the observer or the situation. For example, one person might value risk-taking and view entrepreneurial failure as honorable, while another person values security and views any failure as shameful. The same outcome (a failed business) is assigned different value by different observers. Subjective values are notoriously hard to predict or quantify because they arise from individual psychology and cultural background. Even a single individual may evaluate something inconsistently, influenced by mood or framing. We all “use” subjective values every day – whenever we decide what we like, prefer, or feel is right, we’re often operating on ingrained subjective scales.

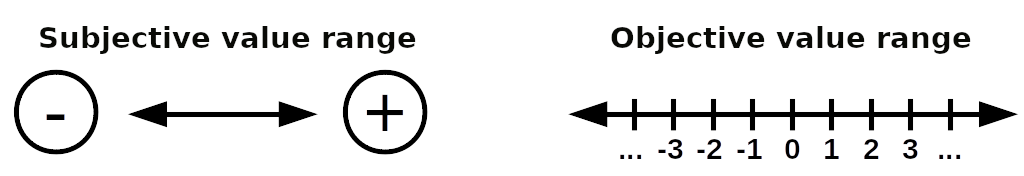

Our subjective values often use a pair of opposites as a basis for comparison, while objective values evaluate with numerical quantities of value relative to a well-defined zero point.

History provides a sobering verdict on the consequences of organizing societies around subjective values alone. Every civilization, religion, and tribe has operated on its own set of subjective foundational values – and these have often directly clashed with those of others. The result has been endless contention: wars, persecutions, and oppression driven by differences in basic beliefs about what is true or important. From the Crusades to the clash of political ideologies in the 20th century, incompatible value systems have fueled some of humanity’s darkest episodes. In a sense, one could say that much of human suffering has resulted from flawed value judgments – groups firmly believing in values that justified conquest, exclusion, or exploitation. The cumulative toll of these subjective choices has been enormous: conflict, injustice, and misery repeated through the ages. Unless we find a way to transcend purely subjective valuation, this pattern seems likely to continue. As one author starkly put it, human life will remain “miserable… until we transition to a culture based on objective values, if that is possible at all”. In other words, the hope of lasting peace and cooperation may hinge on discovering values that everyone can agree on because they are grounded in something more solid than personal opinion or cultural habit.

What might objective values look like? An objective value system would require a reference outside of individual minds – something akin to a natural law of value. To draw a parallel, consider how we use objective measures in science: we agree on units like meters or seconds that are the same for everyone, because they’re tied to physical phenomena (e.g. the speed of light or atomic oscillations). An objective value would need a similar anchor. One idea is to tie values to well-defined physical or biological metrics. For instance, one could propose that the value of an action is measured by its impact on overall human well-being, operationalized through health or longevity statistics. This was partly the ambition of utilitarianism, which tried to measure moral value by summing up pleasure or happiness (a psychological metric) across people. Another approach has been to use money as a proxy for value, since money at least is quantitatively measurable. However, as noted earlier, market prices are ultimately based on aggregate subjective preferences. They fluctuate chaotically with supply and demand and can hardly be called universal or inherent measures of worth. If the value of things were objectively determined by, say, their true cost to sustain human life or ecological balance, then prices would be stable and predictable, not volatile. In reality, we see constant flux: what people are willing to pay for the same house, car, or commodity changes over time and context, revealing the subjectivity beneath the veneer of currency.

One might ask: even if value were objective, could it change over time? Interestingly, the answer could be yes – but in a rule-bound way. Time itself is an objective dimension; something like an apple has an objective value today (nutritional content, etc.) that may be lower a month from now when it decays. So an objective value system could allow values to vary with objective parameters like time or location, but still be governed by uniform laws. The key difference is that the variation would be deterministic and explicable, not whimsical. In economics, we attempt a rough version of this with inflation indices and models, but again, because underlying values are subjective, economists can only partially explain and forecast value changes.

Despite the dominance of subjective value systems historically, the tantalizing prospect of objective values has long been a dream for philosophers and scientists. If humans could agree on an objective value metric (or at least a greatly improved intersubjective one), it could revolutionize society. Decision-making would become more like engineering – identifying optimal solutions based on agreed criteria – rather than a battleground of ideologies. It could “provide relative and fragile stability” to our societies by making our judgments more structured and consistent. In fact, the institutions that have brought some stability to the world – such as the rule of law and monetary systems – succeed in part because they mimic objective structures. Law tries to apply general rules (as if moral value were the same for everyone under those rules), and money provides a single metric (price) that people use in daily transactions. These systems have weaknesses, yet they hint at the benefits of objectivity: we get predictability, fairness (at least in procedure), and easier coordination when we operate with standardized values. However, law and money alone cannot forge the deep social unity we need, because they do not encompass our moral and cultural values in their entirety. Money can’t tell us how to value justice vs. mercy, or tradition vs. innovation, and legal rules only codify values that are already contested at a higher level.

Thus, the quest for objective values remains one of the most profound challenges. Is it even possible to devise a value system that transcends subjective human perspectives? Many attempts have been made, and it is to these we now turn.

The use of subjective and objective values is fundamentally different, but they have one thing in common: we (entities) make the value judgment, and we have the option of making a decision. In the case of subjective decisions, we often rely on the noisy information of our senses, which are loaded with distortions. The figure only illustrates an evaluation according to a single aspect; in reality, many evaluations take place in parallel according to different aspects. The two extreme examples can of course be combined.

Why Attempts to Objectify Values Have Failed (So Far)

Historically, numerous intellectual movements have sought to put morality and values on a more objective footing. The Enlightenment project itself was, in part, about finding universal grounds for ethics in reason and human nature, rather than in sectarian religion or tradition. While some progress was made (e.g. the idea of universal human rights can be seen as an attempt at a cross-cultural value framework), the efforts have fallen short of a truly universal value system. Here we will briefly survey a few notable attempts and why they encountered limitations:

- Utilitarianism and Happiness Calculus: As mentioned, utilitarian philosophers like Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill proposed that we quantify the moral value of actions by their consequences – specifically, by the net happiness or pleasure produced. In theory, one could measure happiness (Bentham even spoke of a “felicific calculus”) and thus compare how good different policies are for society. This was a revolutionary objective approach for its time. However, utilitarianism ran into practical and ethical obstacles. Happiness is not easily measurable or commensurate between individuals – one person’s joy cannot be directly compared to another’s pain on a single scale, especially given subjective differences in temperament. Moreover, pure utilitarian logic can lead to conclusions many find unacceptable (for example, sanctioning the sacrifice of a minority if it greatly pleases a majority). These problems highlighted the difficulty of reducing complex human values to a single metric like “amount of pleasure.” Human well-being has many dimensions (freedom, dignity, etc.) that a simplistic calculus couldn’t capture, leading to revisions and more sophisticated versions (like preference utilitarianism, which tries to respect individual choices). Still, the utilitarian legacy is a precursor to modern attempts to use data (surveys of life satisfaction, for instance) to guide policy – a project ongoing in economics and happiness research.

- Thermodynamic and Biological Metrics: Some scientists have speculated whether value could be grounded in physical concepts such as entropy or energy efficiency. For instance, since living systems maintain order and resist entropy, one might say that actions which increase the order or sustainability of ecosystems are “objectively” valuable. Others have tried to relate value to evolutionary fitness or the flourishing of life. While intriguing, these approaches proved too narrow. The value of human life cannot be reduced to a single physical parameter; our experience of value involves consciousness, relationships, creativity, and other qualitative aspects that are not captured by, say, an entropy formula. A society run solely on maximizing energy efficiency or biomass would likely trample on things we hold dear like individual rights or art – raising the question of whether the metric is really measuring what we mean by value. Thus, purely scientific metrics failed to account for the full complexity of human values.

- Artificial Intelligence and Utility Functions: In the last few decades, especially with the rise of AI, the idea of encoding values into a utility function has gained attention. Advanced AI systems, including reinforcement learning agents, are guided by mathematically defined utility or reward functions that they seek to maximize. Could we program an AI (or a society’s institutions) with a perfect utility function that encapsulates human values? This approach encounters what AI researchers call the value alignment problem. The utility functions are designed by humans, and inevitably they reflect human biases or simplified goals. For example, a hypothetical AI tasked with “maximize human happiness” might interpret that in unintended ways (the classic example: wireheading or forcibly drugging everyone into euphoria, which is hardly what we truly value). AI systems lack common sense understanding of the richness of human values, and any utility function we hard-code is just an expression of our current (often subjective) understanding of what’s good. Indeed, AI value alignment has shown us how hard it is to formally specify all the nuances of human ethics. The lesson from AI is that even hyper-rational agents need a value base provided to them, and we are still stuck deciding what that base should be.

Despite these failures, each attempt has yielded insights. Utilitarianism highlighted the need to account for everyone’s welfare in some aggregate way. Thermodynamic approaches reminded us that any objective value must connect with the physical world (we cannot define value in a way that violates fundamental science or ignores material consequences). AI and decision theory have given us formal tools to think about consistency and optimization in value systems.

A common theme in the failure of past models is the lack of a universally acceptable metric. We have not yet identified a measure of value that all rational observers must concede, cutting across cultural and psychological differences. If such a measure existed – something as clear as, say, “maximize healthy life-years” or “minimize entropy production while maximizing sentient satisfaction” – and if it were grounded in physical reality, we might stand a chance at building consensus. So far, every proposed measure has been either too subjective (happiness, which is felt differently by each person) or too reductive (entropy, which ignores too much of what humans care about).

There is, however, a glimmer of possibility emerging from new scientific paradigms. Advances in information theory, complexity science, and systems theory are giving us tools to quantify phenomena that were previously qualitative. For example, information theory can quantify complexity and order; perhaps “meaningful complexity” could be a basis for value (some argue that life and consciousness create unique complex order in the universe, which could be deemed valuable). Complex systems analysis might help us understand how small-scale interactions yield large-scale well-being or suffering, potentially illuminating objective factors that make societies thrive. Researchers are now exploring whether principles derived from the physical order of the universe – rather than human assumptions – can underpin a new value framework. For the first time, interdisciplinary work is bridging physics, biology, economics, and ethics to ask: are there invariant measures (like energy, information, diversity) that correlate with what humans ultimately value (like survival, knowledge, happiness), and can we formulate those into guiding principles? Such efforts are in their infancy, but they represent a hopeful path forward.

If we succeed in articulating even a few universal value principles (for instance, “any intelligent being would value knowledge” or “any sustainable society must value ecological balance”), it could lay the foundation for a new global ethic. The late astronomer Carl Sagan once spoke of a “cosmic perspective” – the idea that seeing ourselves as part of a larger cosmos might unite us in common values. Similarly, the search for objective values is, at its heart, a search for what all humans (and perhaps all rational beings) share at a fundamental level. From the ashes of the current value crisis, one can imagine a future where humanity has agreed upon core objectives – say, maximizing human flourishing and minimizing suffering in a scientifically informed way – and built institutions on those grounds. This would not magically eliminate all disagreements, but it would provide a shared language of value for negotiation and policymaking.

In conclusion, the modern crisis of values has deep roots in the subjective, fragmented way humans have defined what matters to them. It has led us to a point where we possess incredible technological power but lack the ethical cohesion to use it wisely. The past decade’s turmoil – from the COVID-19 pandemic (which briefly reminded us of the primacy of health and solidarity [3]) to surging geopolitical conflicts – underscores that without common values, our species remains dangerously uncoordinated in the face of global challenges. Yet, this very recognition is also spurring new conversations about how to re-root our values. Scholars and activists are calling for a shift from a profit-centric worldview to one that values well-being, fairness, and our planet’s integrity [3]. Movements for a “wellbeing economy,” for sustainable development, and for cross-cultural dialogue on human rights all reflect an impulse to find shared foundations. The task before us is undoubtedly complex. We may find that truly objective, culture-transcending values are elusive. But striving for more universal and rational values is itself a unifying project – one that encourages global dialogue and cooperation. As the World Economic Forum’s 2025 report cautions, global cooperation is not where it needs to be, and progress on common goals is stalling [8]. To reinvigorate cooperation, we likely need more than treaties and markets; we need a common value narrative. Whether through enlightened self-interest (realizing we rise or fall together) or through discovering some natural law of value, humanity will need to overcome the legacy of subjective value fragmentation. Our very survival may depend on moving from a world of misguided men to one guided by a wiser, shared understanding of what is truly worthwhile – an understanding that could become the sturdy root of a better future rather than the brittle branch of an unraveling present.

References

- Zsolt, Pöcze (2025). The Roots of Our Value Crisis.

- Habermas, J. (1973). Legitimation Crisis. Beacon Press.

- Nicholles, N. (2021). “A Crisis of Values.” Capitals Coalition.

- World Health Organization (2021). Social Isolation and Loneliness – Global report.

- Simply Psychology (2023). “Conflict Theory in Sociology.”

- King, M. L. Jr. (1963). Strength to Love. Harper & Row.

- Ehrlich, P. (2018). Interview in The Guardian.

- World Economic Forum (2025). Global Cooperation Barometer – Second Edition.

- Akaliyski, P. et al. (2023). “Values in Crisis: Societal Value Change under Existential Insecurity.” Social Indicators Research, 171(1).

- Bentham, J. (1789). An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation.

- Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics. Chelsea Green.

- Carney, M. (2020). Value(s): Building a Better World for All. PublicAffairs.